For many roasteries, Colombian coffee equals the Central and Southern departments. Yet it was in the North where coffee production first took place. According to the Manual of the Colombian Coffee Farmer, written by the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia (FNC): “What today is the North of Santander was the first place where coffee was cultivated on a commercial scale and one can say this department is the birthplace of coffee in Colombia. It seems it was already grown commercially in 1760.”

The historic village of Socorro, surrounded by the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes

Reclaiming a long lost status

Despite its vanguard position, Santander lost its protagonism in the turn of the 19th century, a period of recession in the international market. This downturn, added with unpopular government policies of the time was one of the causes of the Guerra de Los Mil Días (Thousand Days’ War), one of Colombia’s most dramatic conflicts since independence. As a department that deeply relied on exports, Santander was hit the hardest and bred a violent rebellion, soldiered mainly by untrained coffee farmworkers. Many didn’t return to the farms.

Today, Santander is the 9th department in order of coffee production in Colombia. In the last century, the Northern states grew again through organic agriculture and strong environmental practices encouraged by the FNC as a commercial strategy. Today, there are 37 thousand coffee farms owned by 32 thousand families. However, the recent period of price recession meant for them that the organic premiums were no longer sufficient to cover their costs of production, launching these families into the specialty wave.

where parchment is kept at mild and stable temperatures

In Europe for the first time

You can find bits of this history when speaking to any of the farmers that are part of Santander’s Coffee Cluster, a group created by Bucaramanga’s Chamber of Commerce in 2016 to make local growers more competitive. The cluster works with a strategic committee on green coffee, roasted beans, and innovative projects. One of their strategies is to help growers transition from commercial to specialty production, an initiative with results you can taste in this Discovery.

Shade-grown coffee is the norm in Santander. The favourite trees are the avocado, the plátano, the guandul, the guamo, the calapo, the nogal cafetero, the balso and various species of citrus trees

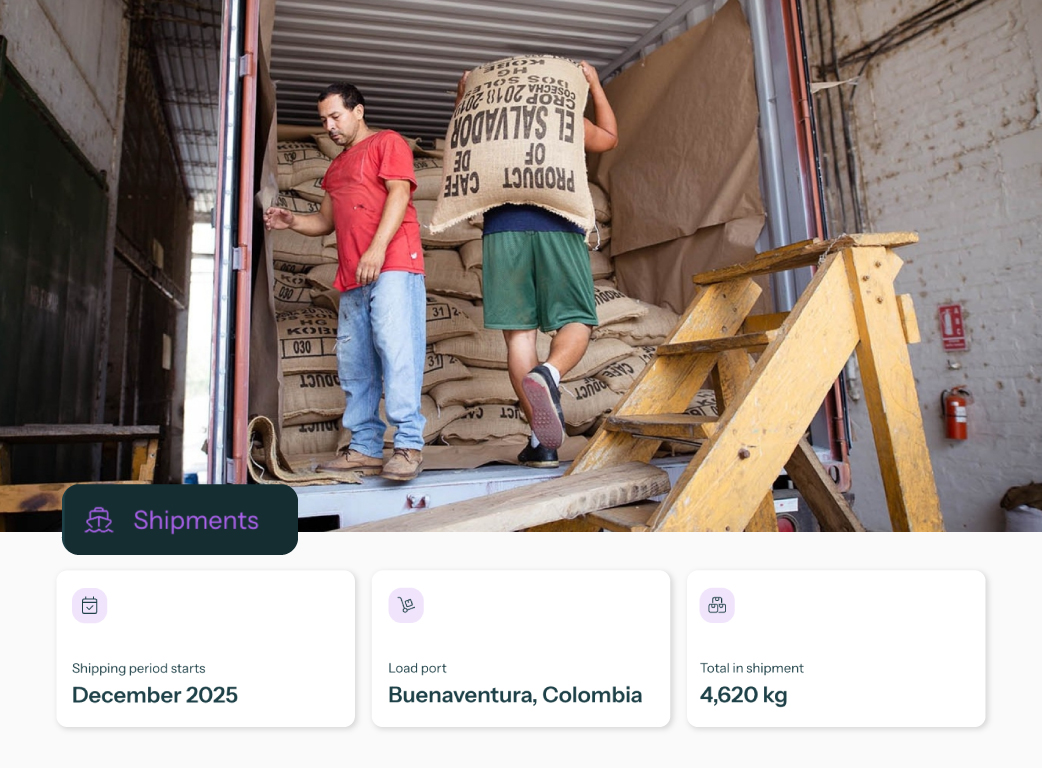

In this first blog about Santander, you may read about 2 of the 8 farmers involved in the project. With different stories and backgrounds, they joined as businesses to promote the department’s coffee and to access the European market. The group visited World of Coffee in Berlin last year to find potential buyers and, despite generating interest, many didn’t have the means to ship small quantities of coffee. The problem is now solved by the Discoveries consolidated container, allowing these coffees to be offered in Europe. For most of them, it will be the first time!

Paola left a job in the city and returned to Socorro to help her father with the farm and roasting business in 2011. Now she is the face of the La Esperanza, innovating in quality with her sisters

Paola Diaz Castillo - Finca La Esperanza

Joaquín Diaz’ firstborn and the eldest of three sisters, Paola, 34, is instinctively responsible, reliable and conscientious. “If I tell you I will do something, I will get it done.” Paola graduated in 2009 as an industrial engineer and worked in Bogotá for a couple of years, returning to her hometown Socorro in 2011 when her dad opened a roastery, Los Comuneros, to help with the family business. “He was snowed under,” she says. She is leading the cluster in what they call “the Algrano project” and has organised the Discoveries on the origin side from the beginning.

The Diaz family runs a complex operation in the historic town of Socorro, 2 and a half hours away from Bucaramanga. They have a coffee farm, a cacao farm, a roastery and a nice little café (where you can eat sweet cheese tarts and taste their cacao honey). Joaquín has been a grower all his life, but La Esperanza became part of the family only in 2004. They have 10 hectares of cultivated land growing mainly Castillo and Colombia with a few new lots dedicated to other varietals such as Tabi, Gesha, Pink Bourbon and Wush Wush.

more quality control and experimentation to their father's farm

More than a feminine touch: how 3 sisters are changing the farm

Working side by side with her father hasn’t always been easy for Paola. They both have strong temperaments. However, Joaquín is happy to let his 3 daughters run the roastery and the post-harvest processing protocols at the farm - the “scientific stuff” as he puts it. Paola, Adriana, and Leidy do everything from managing sales and operations to profiling and quality control at the roastery. They were the ones to bring Brix, pH and humidity meters to the farm.

“The women in Santander are strong and hard-working,” Paola explains. “But, in general, the Santanderano also takes a long time to make decisions and we are not used to working together. All of this makes cooperation harder.” Paola is particularly sensitive to this aspect of local culture because Joaquín has always had an associative spirit. He used to be a part of a group called Kachalu, created to promote organic coffee. He left the group sometime after Kachalu became part of the FNC.

Despite its organic past, La Esperanza is now focusing on different things. “We have been to a couple of international fairs and our biggest take away from it is that the market is not paying that much extra for certifications. The main theme is cup quality. That is why we have been investing in it for the past 3 years,” Paola says.

La Esperanza has a newly rebuilt processing facility with a new depulper and two tanks for fermentation of cherries and coffee in “baba” or mucilage. All their coffees, even the washed lots, undergo a double fermentation process to accentuate sweetness and body. La Esperanza also produces cascara and they are currently developing a recipe of mucilage wine to ensure they find a productive use for all coffee by-products.

Félix Alberto Torres Morantes - Finca Hoyo Frío

ton of green coffee to Australia before turning 25 years old

If you walk into Finca Hoyo Frío midharvest you’ll find Félix Morantes picking coffee with over 10 workers. He doesn’t shy away from the physical labour on the farm that he shares with his brother Ales. Félix has 2 kids, Félix Jr. and Alejandra, neither of which inherited their father’s inclination for manual farm work. Nonetheless, they both found ways to help the family business prosper. Félix Jr. hadn’t turned 25 when he exported his father’s coffee for the first time. It was 2014 and he sent 1 ton of green beans to Australia.

Now a 29-year-old businessman living in San Gil, a touristic town close to the farm, Félix Jr. knew from childhood that picking wasn’t for him. He used to help his dad “correr café” (“to run coffee” as they say), but if you ask him now he’ll tell you there is no way he would do it for life. When it was time to go to university, Félix chose agro-industry and business management, which lead him to a good position in a beer brewing company. However, he couldn’t stay away from the farm for long.

There and back again: a new way to do farm work

At age 23, Félix decided to quit his job at the brewery to work with his dad. He recalls how upsetting it was to see the hard work of his father and uncle being poorly repaid by the local bodegas. As manual work didn’t agree with them, he and his sister Yodi, a designer, founded Café de la Torre, a brand of roasted coffee aimed at generating more revenue for their family’s production in the internal market. Félix hired a white label roaster and started buying coffee from Hoyo Frío at a higher rate than the bodegas were paying.

Picker doing the "raspa", when the last remaining cherries are collected to prepare the trees for the next season. Leaving cherries behind creates opportunity for coffee borer beetle infestations

As the business of coffee was new to them, Félix Jr. and Yodi spent 3 months studying at Escuela Nacional de la Calidad del Café in Quindío, which Félix funded himself for them both. He also started looking into exporting at that time. Getting an exporting license wasn’t a straightforward process though. Félix says, tactfully, that encouraging is not a word he would use to describe the national officials and that bureaucracy is a barrier. “They kept saying the documentation wasn’t correct. I had to go to their office in Bogotá and make a scene to sort it out,” he recalls.

Sofia, Ales youngest daughter, holds a flower of balso negro with a dead bee inside. The FNC used to encourage farmers to grow these trees before finding out its deadly impact on the bee population

After sending his first ton of coffee to Australia, Félix has shipped and flown coffee to countries in America, Europe, and Oceania, making his proud father prosper. With an annual production between 8 and 10 tons, Hoyo Frío now sells a substantial part of their coffee to Café de la Torre, micro-lots to international customers and lower grades to the FNC.

Despite its modest infrastructure, the farm is preparing itself to increase production with 2 more hectares of cultivated land and improve processing by buying a modern depulper. They also have lodging at a second farm to receive foreign visitors.

.jpg)

.png)