Over the last few months, the commodity market has been waiting for one thing above all else: rain in Brazil. Without it, coffee prices have soared to 13-year highs, and there's little relief in sight. Will there be enough rain to calm the C-market? Let’s look at what's happening.

In this article:

- Can the coffee plant’s stress damage be reversed? While upcoming rains in Brazil may help, the damage to coffee crops has already been done, and only consistent, perfect weather can minimise the impact.

- Averaging vs perfect timing: Roasters waiting for coffee prices to drop may be waiting too long—averaging prices over time could be a smarter move to secure supply in the middle of volatility.

- Ports are already too busy: Congestion at Brazilian ports is already delaying 70% of shipments. The expectation now is that November and December could bring even longer waits as containers pile up.

After record highs, prices are staying strong

After hitting a 13-year record last week for the second time, you’d think coffee prices are going to fall any time now. But there’s nothing on the horizon pointing to substantial price changes.

It’s not that the commodities market isn’t reaching a limit. In Brazil, intermediaries are putting up more money for margin calls and extending payment terms to producers—from seven days to 30 days. That’s unheard of. Arabica and Robusta prices are high, and the market is exhausted, according to a Safras & Mercado analyst.

But the weather doesn’t care about any of that.

When prices are unpredictable as they’re now, the recommendation from producers and analysts is to buy slowly at different prices instead of waiting for the C-market to hit a magic number.

Price averaging

In coffee trade, this is called DCA (dollar-cost averaging) or simply averaging.

This is a strategy that coffee traders use to manage price risk. Instead of buying all the coffee needed for a season at one time, they buy smaller amounts gradually and create an average price over time. This way they can benefit from when the C-market is lower without risking supply shortage when it’s higher.

Double wait: Brazil’s flowering and Vietnam’s harvest

.png)

Over the last few months, the coffee market has been waiting for two main events: coffee flowering in Brazil (starting in September) and the harvest in Vietnam (starting in October). Both are heavily dependent on the weather.

Brazil is currently experiencing one of its worst droughts in recent history. Meanwhile, Vietnam is facing heavy rains and even a typhoon. Let’s take a closer look at what's happening in each country.

Vietnam: from drought to downpour

There hasn't been much good news coming out of Vietnam. First, there was a long drought, followed by months of heavy downpour—and then Typhoon Yagi hit.

To make things worse, farmers are reportedly replacing coffee crops with other fruits like durian, which is popular in China.

What’s the impact of all this on coffee production?

- Smaller harvest expected: Reports suggest Vietnam’s upcoming harvest will be 10-15% smaller due to the extreme weather. Drought affected bean development, and now, heavy rainfall could interfere with picking and drying.

- Logistical challenges: The rains also make it harder to transport coffee, delaying the start of the shipping window from November to December.

- Price impact: The new harvest should eventually help ease prices when the crop becomes available and uncertainty fades—but that won't happen until after Christmas.

And it’s not just Vietnam. Indonesia, which produces around 10% of the world’s Robusta, is seeing more of its production absorbed by a growing domestic market, further reducing Robusta’s availability.

Brazil: praying for the rains

In Brazil, September came and went with no real rain. Yes, there have been some isolated showers. But at this stage of the coffee tree’s cycle, it’s not just about whether it rains anymore—it’s about damage control. The next crop is already affected.

.png)

The weather forecast isn’t bad—rains are expected in October and November. But coffee plants are more stressed than they should be. After such a long, dry, and hot period, the weather needs to be perfect for plants to recover.

Have you seen perfect weather anywhere recently? Didn’t think so. Without enough rain, the pressure on supply will support high prices with little relief on the horizon.

Like being inside a hot oven

"2020 was our last big crop year. In the South of Minas, we haven’t harvested much since," says Alessandro Hervaz, vice-president of Coopervass.

“This year, the weather’s been weird. We had lots of heatwaves in the summer—it felt like being inside an oven. Then, in May, the temperature usually drops, and the plants go dormant. This May, it was freakishly hot. The plants never went into dormancy.”

The problem isn’t just delayed rains and flowerings. Alessandro even saw trees flowering without rain, and in the middle of the harvest—which is highly unusual.

Will the flowers set?

“So the plants are already stressed, right? And we had these small bursts of flowering. First question: will the flowering set?” asks Alessandro.

“It might be a wasted shot. If the weather stays this warm, the flowers might abort. And then, the plant will use up energy trying to hold onto the seed, leaving less energy for new flowers. If it rains, the impact will be minimised. But it’s a question mark. It has to rain a lot more.”

.png)

Even if it does rain, flowers don’t guarantee production. Traders know that.

So while the market may adjust slightly if the rains come, prices aren’t likely to drop dramatically—unless something unexpected happens, like the dollar gaining strength against the real. That’s a long shot, especially since the dollar lost strength after the Fed cut interest rates in mid-September.

Pinhead stage: the next critical period

Four to six weeks after flowering, the cherries enter the pinhead stage, when they start to form. This post-flowering period is crucial. It’s when the plant is most vulnerable to abortion and when we start seeing next year’s crop take shape.

Had this been a normal year, a good flowering would indicate a strong crop. But this year has been far from normal.

“The farms are all looking rather sad. In the town of Cerqueira, near where I am, there’s a water reservoir. I saw a video of farmers watering the plants with a tractor full of water from the dam,” says Bruno Andrade of Trust Coffees.

“We have to pay attention to what the weather is showing us and stop waiting for a miracle that will make the market drop. Because that’s what it’ll take: a miracle.”

2025/2026 crop outlook

According to Bruno and Alessandro, the next harvest—the 2025/2026 cycle—isn't looking great. The damage is already done, and while some of it can be reversed, there are too many variables and high risks.

At this time of year, expectations about the next Brazilian crop have a big impact on prices. Lower production forecasts put pressure on supply and make farmers cautious about selling.

"I see roasters waiting for the market to drop below US$2.00/lb, and I’m like… forget it," says Bruno.

“Maybe, if the dollar hits six Brazilian reais, because the dollar has a strong hand in coffee prices. But we had some rain this weekend, and on Monday the market went up again. And farmers are not desperate to sell, so they’re not taking just any price. Plus, they know there's a risk. If rain doesn’t come, they will need more money this year to cover next year’s loss.”

In areas where productivity hasn’t been high recently, the pressure to make money is even greater.

“Let’s be honest. In 2022 and 2023, we ended the year in the red—costs went up, and volume went down. Now, we’re making money, but we’re paying bills from the last two years. What about next year? We might have to stretch one year’s profit over four,” Alessandro says.

.png)

Commodity coffee selling fast

Despite all these challenges, commodity-grade coffee is selling like water in the desert.

Brazil had its best August ever for coffee exports, and the new crop is moving quickly. In July and August of 2024, volume sold was up 11.8% compared to 2023. And in the first eight months of the year, exports increased by 40%, with Europe increasing its share of imports by 10%.

This indicates that buyers are shifting from a “hand-to-mouth” approach and are starting to stock up, anticipating reduced supply in the 2025/2026 cycle. They're also buying protective stock ahead of the new EUDR regulations.

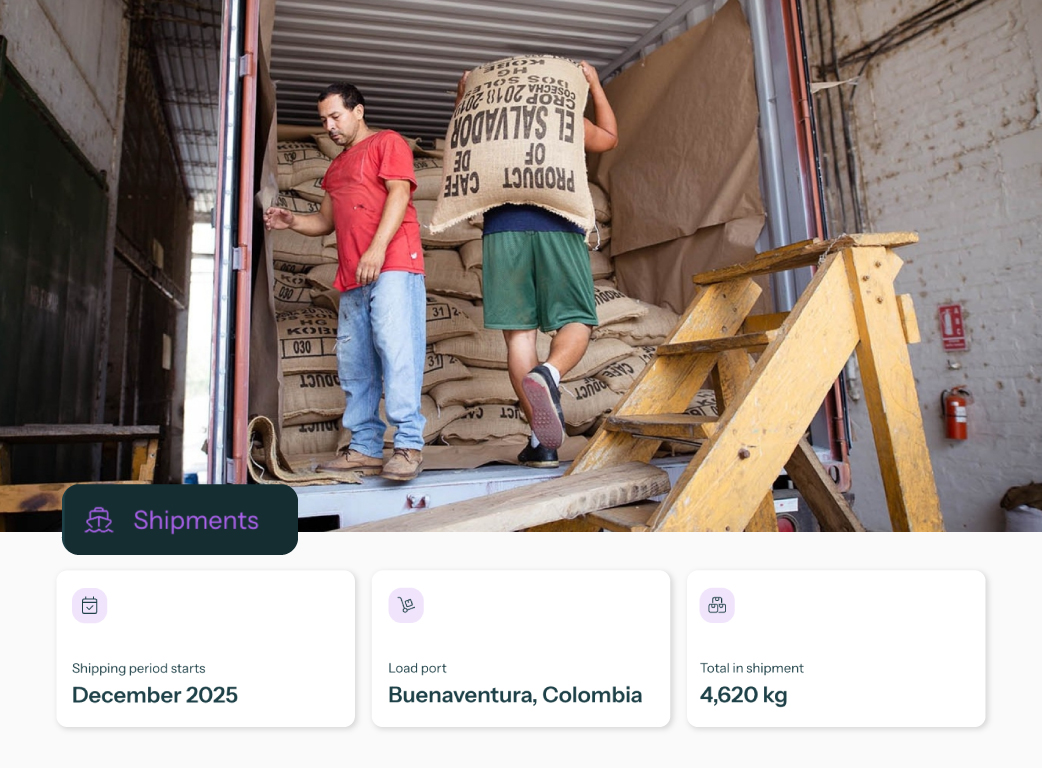

Chaos at the ports

With only three months until EUDR takes effect, traders are importing as much as they can. Brazilian ports, which usually only face traffic disruptions in November and December, have been experiencing delays since August.

According to Cecafé, 70% of all coffee shipments were delayed. At the Port of Santos—Brazil’s largest—nearly 90% of shipments had to change dates, with delays of up to 29 days. Specialty coffee buyers are getting stuck in the chaos, especially those holding off on orders in hopes that prices will drop.

“Holding the order creates a lot of problems,” says Bruno. “Roasters can’t wait and want their coffee delivered in a month. But then we have issues at the port. There are loads of containers stuck at Santos, costing exporters money. And at the end of the year, it’ll get even worse.”

Roasters are now facing the inevitable—prices need to go up. With coffee costs still climbing, it's getting harder to absorb the increase without passing it on. Just like in Italy, where a simple €1 espresso might double in price, specialty roasters need to face the reality that holding steady isn’t sustainable. Many are already adjusting their prices, and for those still waiting, it might be time to follow suit.

.png)