It’s Arabica coffee season in Uganda

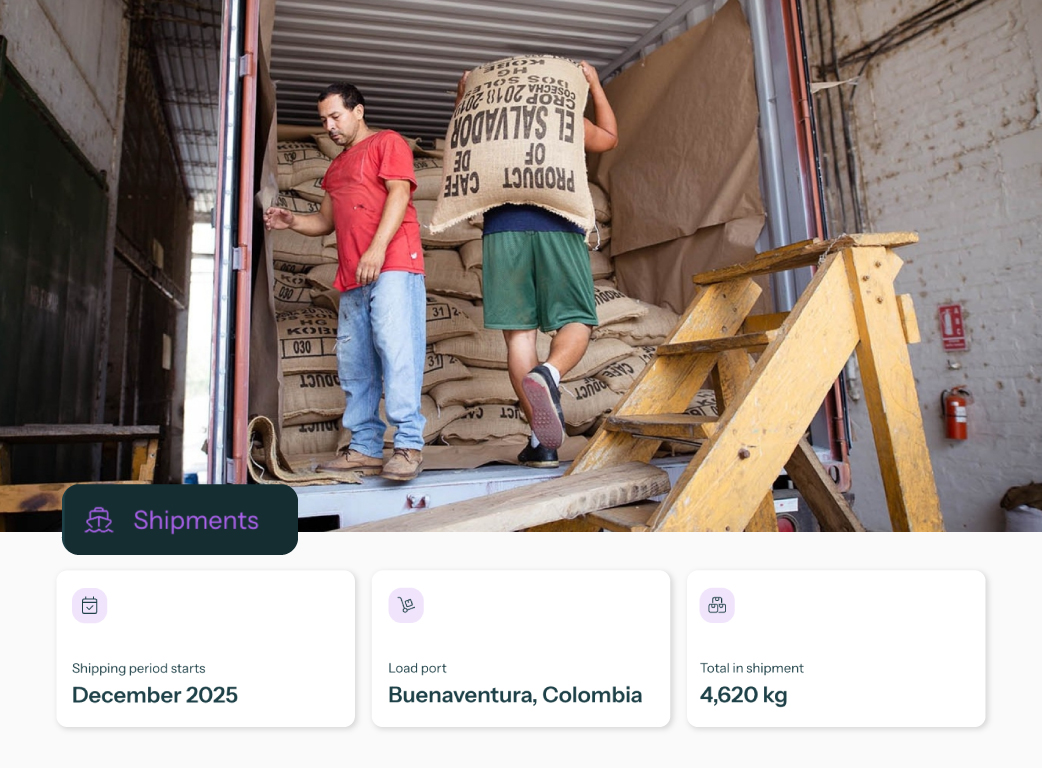

Uganda’s Arabicas are in season, with farmers harvesting from Mount Elgon in the East to Mount Rwenzori in the West. The harvest started in September and will continue through February. We'll have a series of shipments to Europe and the United States over the next eight months, according to exporters' production timelines.

On Algrano, you’ll find lots from two small and native-owned Uganda’s cooperatives:

- Mt Elgon Agroforestry Communities Cooperative Enterprise (MEACCE): samples should be ready to cup by the end of December, and the coffee is expected to hit warehouses by June 2025 (Europe only).

- Mountain Harvest: samples will be available in March for shipments leaving Uganda between June and July. This should be available to release around October (Europe and US available).

To give you a picture of this year’s harvest, we caught up with Mountain Harvest, who operate across Uganda, and MEACCE, who focus on Mount Elgon coffees. Here’s what they had to say about this cycle's challenges—and what might impact your sourcing decisions.

.png)

Less Arabica to go around

This season, there’s less Arabica coffee coming from Uganda. The 2024/2025 marketing year is an "off" year in the biennial coffee cycle, but the weather has made things even trickier—especially when you consider the growing demand for the country’s coffee. Irregular rains led to early flowering, only for the rain to stop abruptly, causing a lot of flowers to abort.

If you’ve seen reports suggesting Uganda’s coffee output is increasing, that’s likely thanks to Robusta. The USDA predicts a slight rise in Uganda’s overall coffee output due to Robusta’s dominance, which makes up over 80% of the country’s production. Improved farming techniques and new high-yielding Robusta plants are behind this rise—not Arabica.

Luke Wepukhulu from MEACCE puts it plainly: “Production is low on the mountains, and we’re projecting a small crop. Some zones didn’t get any coffee at all this year because flowering wasn’t good. We had rain in January and February when we should’ve had sun.”

.png)

Adapting to the unpredictable

Processors are adapting as best they can. Last season, too much rain meant exporters had to redry parchment coffee. This year, it’s the opposite—dry, hot weather that makes those costly investments in drying infrastructure seem like money down the drain.

“The issue with climate change is that the weather isn’t predictable,” explains Kenneth Barigye from Mountain Harvest. “Last year, we didn’t have enough driers because it wouldn’t stop raining. So we built more solar driers. Now it’s 31 degrees in Mbale, and it’s supposed to be raining. All that investment to protect the coffee from rain won’t pay off this season.”

Mountain Harvest has adjusted its drying processes, centralising the work to create more consistency despite the unpredictable climate. Nico Herr explains: “Processing managers used to bring coffee down from micro-washing stations to dry at our warehouses, all fighting for space and labour. Now, our central team manages drying across different stations, and we’re seeing more consistent results.”

Over at MEACCE, they’re looking to buy coffee in cherry form this year to have more control over quality. Luke mentions that coffees cupped by the end of October were scoring below 84 points—unusual for the region. Kenneth also notes a dip in the quality of competition coffees across Uganda in 2024.

In Uganda, most coffee is sold in parchment. “Farmers prefer selling parchment because they get paid in bulk,” Luke explains. “But they struggle with sorting and often prefer to sell cherries, less labour. intensive.”

.png)

Traders’ market share in Uganda

Besides climate challenges, Ugandan coffee organisations are up against an old predicament—price struggles—largely due to internal dynamics in the country.

Since 2017, prices for coffee parchment have been rising steadily. “Parchment prices have more than doubled, from 5,500 to 13,000 Ugandan shillings (UGX),” says Kenneth. This means farmgate prices went from about US$1.90/kg in 2017 to over US$4.30/kg in 2024.

But it’s not just international market demand driving this increase. While there’s more interest in Ugandan coffee, the situation here mirrors other countries dominated by large multinational traders.

In Uganda, the top ten exporters hold over 75% of the market share. Most are multinationals with branches at origin, trading not just coffee but other commodities. With better access to finance and cheaper credit lines, these large companies drive up prices to secure supply, sometimes aggressively.

“Are higher parchment prices good for farmers?” you might ask. In a way, yes. “The Ugandan coffee farmer is the highest paid farmer in the world,” Kenneth points out. But that doesn’t mean the sector is sustainable.

.png)

Double the price vs. income diversification

With most Ugandan coffee coming from smallholders with less than half a hectare, prices would have to be double today’s rates to ensure farmers a decent livelihood. For Mountain Harvest, which pays farmers 30% above the local rate, that would mean a farmgate price of over US$11/kg for basic-quality parchment.

In 2019, Mountain Harvest conducted a survey to assess what would help farmers afford a decent standard of living. The answer was double the farmgate price, double the landholding, or diversify income. “Doubling the price is tough,” Kenneth says. “And doubling the land? Not possible—there’s not enough land available. Income diversification is the only way.”

Mountain Harvest is now helping farmers broaden their income by planting high-value crops like avocado and macadamia, on top of other products like honey and vegetables.

.png)

It’s not (just) about the C-market

Ugandan coffee prices don’t track the C-market like in Brazil. “The C-price doesn’t even cover the cost of cherries to fill a container,” Kenneth points out.

“The farmgate price here isn’t linked to New York. So, when buyers tell me my price is too high, I say, ‘I don’t grow coffee in New York!’ I wish they’d ask me about the cost of production.”

Kenneth admits he’s often puzzled by how large exporters make a profit on commodity coffee sales in Uganda. Luke sheds some light on this: economies of scale and blending.

“Large traders have more money,” Luke explains. Their costs per unit are lower, and they get cheaper financing. Some, Luke says, blend different quality coffees. “A middleman might buy parchment at 500 UGX from some areas and at 1,400 UGX in others, like Mount Elgon. They blend and sell at 1,000 UGX and still profit.”

This practice leaves farmers with the impression that quality doesn’t count. Luke believes this is part of a calculated effort to push smaller exporters out of the market by driving up costs. “If we all get priced out, the big players who remain will dictate future prices. It’s a monopoly,” he says.

.png)

What does it mean to support Ugandan farmers?

Unlike multi-commodity traders, local exporters like Mountain Harvest and MEACCE invest in capacity building. MEACCE is introducing a micro-financing programme for farmers to tide them over in the off-season and supplying depulpers and solar dryers to improve parchment quality.

Mountain Harvest also provides micro-loans for farmers, paired with financial training to help them manage cash flow and invest in productive assets, such as farm tools. Kenneth hosts planning sessions with all farmers who work with the organisation to set seasonal priorities. In Mt. Rwenzori, they’re working with local entrepreneurs to build a group of young, skilled coffee aggregators who will learn to run viable coffee businesses.

“Most of Uganda’s population is under 17, and they don’t see opportunities in coffee,” Kenneth explains. “We need a new generation willing and able to continue production.”

While multinationals might invest in infrastructure and certification, they’re typically focused on yield and efficiency—not on creating local capacity or direct market access. For genuine progress, Uganda’s coffee sector needs holistic systems, where farmers have their own leaderships and independence.

We recommend reading the 2024 Farmer Thriving Index by 60 Decibels to understand more about the livelihoods of Ugandan farmers. The report was produced with support from Mountain Harvest.

Feature photo: Makali Community Station at Mt. Elgon by Mountain Harvest

.png)