“It’s a war”: why it doesn’t matter that the price is high

Climate change is catching up with coffee, and this year’s harvest in Central America shows just how much. First, no rain. Then, way too much rain. Picking schedules are in chaos. The weather’s unpredictable, forcing producers to mobilise pickers fast. But what if there’s a labour shortage? Welcome to Central America today. And it’s still raining.

That’s chapter one. Globally, supply is tight and demand is reacting. Multinationals are swooping in like birds of prey, buying despite high prices to secure what’s available. “It’s a war,” says Felix Monge from CoopeLibertad, Costa Rica. “Everyday someone increases their price and we have to match.”

Demand is so high that coffee is being contracted without samples. Costa Rican cooperatives have sold 20% more coffee than usual. In Honduras, anything scoring below 84 points might sell out in six weeks.

Now, cooperatives in Honduras, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua have enough stock. If you’re a roaster, it might feel early to buy. This year, it ain’t. Also, news from Brazil isn’t great, and waiting for prices to drop is a gamble. El Salvador and Guatemala still have picking left to do, but buyers will be there before you know it.

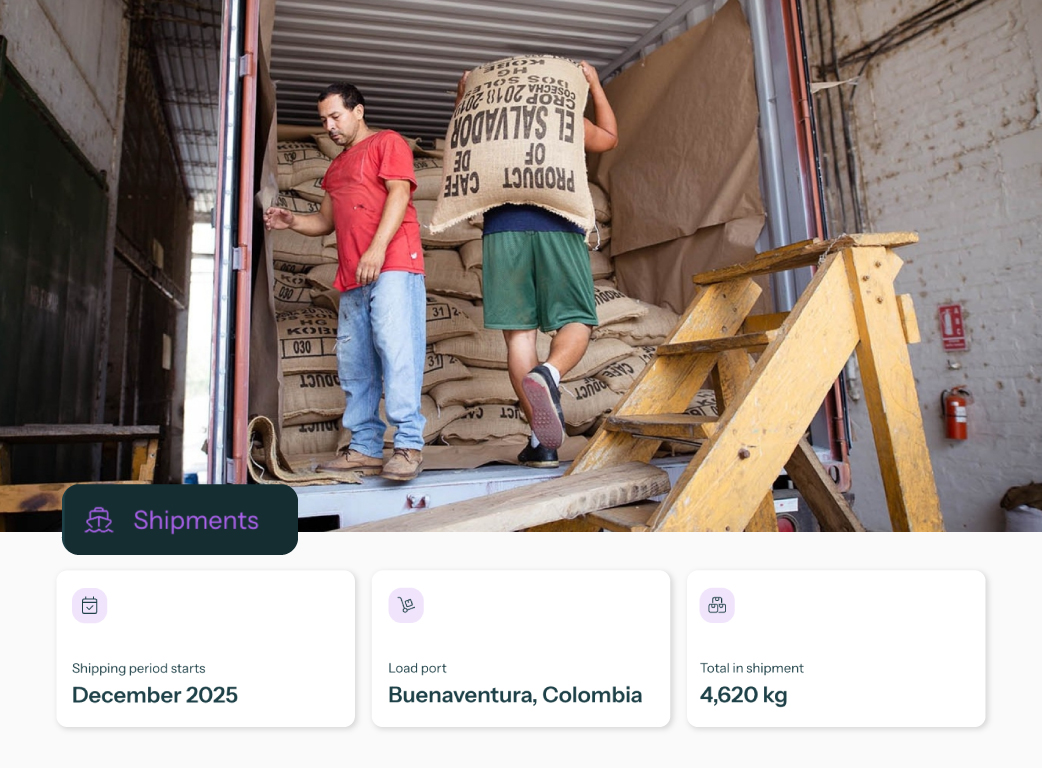

That’s why Shared Shipments from Central America will leave earlier this year. Orders for these early containers need to be placed by late February. This might sound alarmist (it’s not), but don’t wait for samples; we’re managing quality and price risks as always.

No shelter from the sky

You’ve probably heard of El Niño’s influence in 2024, bringing droughts and heat to pretty much all Latin America. Or about tropical storm Sara, which hit farms just before harvest, causing production losses from Guatemala down to Costa Rica. But tropical storms are a regular feature in this part of the world. And El Niño is cyclical. So why say climate change is catching up? And why does it matter?

We asked Juan Marquez, an advisor in agricultural projects at Lean Coffee Management, El Salvador, to break it down. “Weather events are more disruptive to coffee production today because the baseline temperature is hotter. The evaporative demand on plants is much higher now,” he explains.

Evaporative demand refers to how much water the environment "pulls" from plants and soil. Warmer temperatures, stronger solar radiation, and wind speed are all factors driving this demand up.

Put simply, high evaporative demand means plants lose water faster. By the time the rains arrive, coffee plants are already stressed. It’s like starting a new project when you’re burned out.

Lean Coffee works with farmers across Colombia and Central America, including MAV Coffee. To give their farms a fighting chance, they’ve been renovating trees, improving soil coverage, pruning smarter, and testing resilient varieties like Obatã and Arara. Despite all that investment, MAV is seeing bigger losses than they expected just weeks ago.

El Niño, La Niña, and more

Juan also highlights another cyclic event shaping Central America’s weather: the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). This long-term climate pattern in the Pacific Ocean affects temperature and rainfall.

The PDO flips between warm and cool phases, and it interacts with El Niño and La Niña. Sometimes it fuels their intensity; sometimes it dials them down. But here’s the problem: oceans are warmer, making PDO less predictable, and extreme El Niño and La Niña events are happening more often.

“El Salvador is basically a coastal country, so we’re wide open to this,” Juan explains. “Once, the PDO and La Niña combined to give us 60 days of rain. It was a disaster. But the irregular rains we’re seeing now are just as bad. And this could last another ten years.”

We’re explaining this because the weather events behind today’s market volatility are not a short-term problem. And even if we don’t face tight production levels every year, weather uncertainty is a new reality in coffee, affecting supply and prices for roasters.

Compressed harvests, shorter maturation, and fallen cherries

In Costa Rica, this year’s harvest was supposed to be a comeback story. After a record-low production in 2024, things were looking up. Since tropical storm Sara, ICAFE revised their forecast down by 200,000 quintales. But that wasn’t the end.

“We were meant to have four solid weeks of dry weather during the peak harvest,” says Felix Monge. “But the rain never stopped. Now there’s a big risk of cherries dropping, especially with the lack of labour.” It’s the perfect conditions for everything to go wrong.

“It’s not even that we have too much rain,” Felix continues, backing up Juan’s overview, “but it’s falling at the wrong times. In many regions, it was too strong at the end of the year, right when the coffee was ripening. If the bean is green, no problem. But when it’s ripening, there’s a big risk.” He’s convinced this isn’t bad luck. “The concentration of rain we see today can only be explained by climate change.”

Hop the border to Nicaragua, and the Arabica harvest was delayed by five weeks. May rains didn’t come until June. Farms at lower altitudes, that had already flowered back in February, aborted due to too much solar radiation. “When it started raining again in June, these farms flowered again, but less,” explains Manfred Guenkel from Sajonia Coffee. “They started harvesting only in November, at the same time as higher up farms.”

Manfred adds that, luckily, rain during the harvest hasn’t been a problem this year in Nicaragua, which helps with quality. But the harvest is concentrated there too, and pickers are expensive.

Labour shortages: from headache to migraine

Labour shortages have been a headache across Latin America for years, but this harvest, they’ve reached migraine levels. In Nicaragua, the government announced new laws which make it harder for workers to migrate to Costa Rica. “We’ve had to establish new connections with indigenous Panamanian groups to secure workers,” says Felix Monge. These last minute arrangements result in extra costs.

You’d think that with fewer workers leaving Nicaragua, labour would be easy there. But no. Manfred explains: “Pickers watch coffee prices too. And they ask for more money.” Farmers are having to sweeten the deal. “Better housing, internet, TV, parties, and even raffles,” Manfred says. Some workers are earning up to US$80 per quintal (46 kg of green).

There’s a different version of the same story in El Salvador, where a short maturation window means green, ripe, and overripe cherries all sit together on the same branch. Producers have to mobilise workers at a moment’s notice to get ahead of the weather forecast. “One of the farms had picking scheduled for Monday, but with rain predicted over the weekend, we had to go earlier,” says Irene Villavicencio of MAV Coffee. “It’s awful. You wait for the coffee to develop the right amount of sugars. Then the rain comes, and they start fermenting.”

Irene’s taking careful steps this year. Buyers are already asking for offers, but she’s holding off until she knows her profiles are consistent. “There are a lot of dry and immature beans. If farmers don’t float their coffee, they will end up with quakers,” she warns.

She’s also keeping a close eye on brix levels for her Naturals. “I always want a high brix for sweetness, but if I can’t reach it, I have to do something different.” Anaerobic fermentation could be her backup plan, but she’s got mixed feelings about it. “A good fermentation can save a Natural with low sugars. But anaerobic coffees? There’s a stigma now. It’s become a bad word.”

Futures are up by 80%. Differentials are also higher

Looking at all this, multinationals are going all in, even buying cherries where they’d only buy parchment or green. The market has reached a point where the price tag doesn't matter—buyers just want coffee. And they’re throwing around big differentials to seal the deal, which is rare when market prices are already this high. “Companies with December export contracts were buying coffee desperately,” says Manfred Guenkel.

Here’s what’s happening: high differentials are doing double duty. On one hand, they make asking prices more attractive, speeding up negotiations. On the other, they give producers breathing room—enough to pay farmers more if prices climb further. The gap between FOB and farmgate prices is also wider than usual due to high financing costs and the sheer unpredictability of it all.

For roasters, Central America’s FOB levels might come as a shock. It’s easy to wonder why specialty prices have risen when producers are earning more. But let’s put it in perspective: futures prices are up 80% compared to January last year, and country differentials are climbing too. Oh, and don’t forget higher costs and quality premiums.

Speculation is turning up the heat. “Some people are saying prices will hit US$4.00 per pound,” says Juan Marquez. “Producers are holding onto their coffee until the last moment, selling only enough to cover costs. There’s a lot of confidence in this rumour that there’s no coffee.”

Not just another boom-and-bust cycle

This will be a tough year for coffee—there’s no way around it. Whether you’re buying forward or spot, coffee is scarce. Forward buying offers a bit more security, as traders are focused on fulfilling contracts rather than packing offer lists. But roasters can’t sit around hoping prices will drop, especially with what we’re hearing from Brazil.

“We understand that it’s in roasters’ nature to expect prices to drop,” says Manfred Guenkel. “It was the same last year when the market was at US$1.60/lb. Then it shot up to US$2.30/lb, and those who bought late paid the price. This year might be the same. With the production levels we’re seeing, if forecasts are revised down, prices could go even higher.”

For the exporter, this isn’t just another boom-and-bust cycle. “This is the new reality. Buyers will have to adapt their cost structures, and consumers will need to accept that a cup of coffee isn’t as cheap anymore.”

Coffee is at a crossroads

If there’s any good to come from this, it’s that we’re being forced to face long ignored realities. “Coffee is bankrupt,” says Irene Villavicencio. “People don’t want to be in coffee because it’s not profitable, and one reason is that we do things out of tradition and refuse to think outside the box.”

For Irene, this moment is an opportunity for Salvadoran producers to rethink how they farm. “There’s this mindset here that Bourbons and Pacas are what make our country special, but we’re being forced to look at other varieties. It’s mind-blowing how resilient other coffees are,” she says.

She also sees a shift in how producers value labour. “The weather’s unpredictable, so we need a team at hand. That means better pay and better conditions,” Irene says. “We’ve been working with a group of women for the past four years, and their work has never been more valuable. Colour isn’t a reliable measure of ripeness anymore. An experienced picker knows what’s ripe by how juicy it feels and how easily it pulls from the tree. That kind of skill is life-saving.”

For Juan, this year puts coffee at a crossroads. “Buyers need to create purchasing mechanisms where the producer is more present,” he says. Juan has watched farmers walk away from coffee year after year. “The farms that survive will be the ones with stable sales, fair prices, and strong relationships. And the same goes for roasters. The only ones who’ll survive are those who can guarantee a stable, quality product.”

Important dates

Custom containers

Orders of 150+ bags can be shipped in custom containers at the time that suits you best, starting in February for the origins listed here.

Shared shipments

Nicaragua

Vollers, Bremen - Germany

The container closes on February 28th.

Continental, New Jersey - USA

The container closes on April 15th.

Click here for samples (from January).

Guatemala

Vollers, Bremen - Germany

The container closes on February 28th.

Annex, California - USA

The container closes on May 15th.

Click here for samples (from March).

Costa Rica

Vollers, Bremen - Germany

The container closes on February 28th.

Vollers, Bury St. Edmunds - UK

The container closes on May 15th.

Annex, California - USA

The container closes on May 15th.

Click here for samples (from late January).

El Salvador

Vollers, Bremen - Germany

The container closes on February 28th.

Click here for samples (from March).

.png)