In this article:

- The coffee harvest in Brazil started about a month earlier in most places and is now 80% complete. Production levels are still consistent with an on-year of the biennial cycle, but forecasts are being revised down.

- Availability of specialty coffee volume lots and fine commercials will be affected by smaller screen sizes and uneven cherry ripening. Producers need to process more cherry this year to fill up a 60 kg bag.

- Pulped Natural production suffered because high percentages of cherries were too dry at the time of harvesting for de-pulping. They’re being processed as Naturals instead.

- Brazilian domestic stocks are being emptied thanks to high export volumes in the first half of the year. This could limit offer availability until the end of this cycle in June 2025, putting pressure on prices. ICE-monitored stocks are, however, recovering.

- Price volatility is expected to continue until at least September when spring showers trigger flowering and the next crop starts taking shape. But La Niña could start between August and October, delaying the start of the rainy season.

Introduction

You’ve probably heard that the average screen size of coffee produced in Brazil this year is smaller. You might have seen photos of coffee plants at harvest too, with green, ripe, and overripe cherries on the same branches. So, what’s going on here? And what does it mean for the price and quality of green coffee heading to your roastery?

Let's dive into what’s been happening in Brazil this season and how it’s shaping the coffee market. We’ll also touch on what to expect for the next flowering season starting in September, as that’s likely to influence price movements before the end of the year.

This harvest report was written with input from coffee producers who sell coffee through Algrano to get green buyers up to speed. You’ll get the backstory of what’s on your cupping table, the factors behind the offers on the marketplace, and the forces influencing prices. Use this as a base for your conversations around coffee lots and prices with your account manager and producer.

Coffee’s maturation window is shorter

Brazil has already harvested more than 80% of this year’s coffee. This is the fastest crop in the last five years, thanks to an early start and a shorter maturation window—the time it takes for cherries to go from green to ripe.

Why is this happening? Well, it’s all about the heat. Average temperatures in Brazil have been higher than usual, speeding up the process. “The whole coffee cycle, since the flowering, happened faster because of high temperatures. Normally we have cold nights with 5℃ or 6℃. This year they were very few,” explains Derio Brioschi of Farmers Coffee in Espírito Santo.

.png)

In Derio’s mountainous region, the harvest is manual and relies on seasonal workers. “I was caught off-guard. If picking normally takes a month, we only had 15 days and not enough people in the fields,” he reports. Farmers in his region lost between 20% to 30% of their normal ripe cherry volume.

But most Brazilian coffee is mechanically harvested, so this shouldn’t be a country-wide issue, right? Not exactly…

Lower availability of Pulped Naturals

There were two main flowerings in Minas Gerais last year, and they happened far apart from one another. Like the maturation window, this is also linked to heat and lack of rain.

“If you wait for the cherries of the second flowering to ripen, those of the first one will be overripe. But if you harvest based on the first flowering, you end up with too many green cherries. We could go with the machines twice, but it’s very hard to reach an optimum maturation peak even if you adjust the harvesters,” explains Allan Botrel of Sancoffee in Campo das Vertentes, Minas Gerais.

The impact on production is clear. After cherries are sorted for ripeness, there will be less volume of fruit to process into higher quality lots that fit specialty standards. Allan adds that Pulped Natural lots will be scarce because of the sheer amount of dry cherries harvested.

.png)

“In Campos das Vertentes, we normally do Pulped Naturals until mid to late July. This year, some people stopped wet processing at the end of June. The cherries were so dry they were turning into ‘raisins’. And then you can’t put them through the depulper. It’s beyond the phase when the machine can separate the seeds and remove the mucilage.”

In Espírito Santo, where most of the production is Pulped Naturals, Derio also says the supply of Naturals will be higher this year. “With overripe cherries, we can still produce good quality Naturals. But we’re also seeing a lot of defective overripes because the region is humid. That coffee can’t be left long to pick.”

Screen size and cherry-to-green ratio

The screen size of Brazilian coffee is also being affected by the heat. “The winter hasn’t been cold, so this might have accelerated the plant’s metabolic process, speeding up maturation and yielding seeds that didn’t fully form. So we end up with lower screen sizes,” Allan clarifies.

In the commercial market, coffees labelled as screen 17/18 are prised. That’s the grade that goes into Fine Cup lots, preferred by large roasteries because the consistent bean size makes it easier to roast evenly in big machines. While it does well for consistent roasting, screen 17/18 doesn’t necessarily score higher on the cupping table.

Metabolic changes hide another problem that became more evident as the harvest progressed in Brazil. Bean development led to a higher cherry-to-green ratio. This means you need more cherries to fill a 60 kg bag of green coffee.

.png)

“A bica corrida [pre-milling green] processed as Pulped Natural has a yield factor of, let’s say, 75% on screen 16 up. In some places, this percentage dropped by 15%. I heard rumours of 30%. So you spend more coffee to get to an exportable grade,” Allan explains.

For Derio, who works with Arabica and Robusta producers, it’s the same story. The ratio dropped, beans are smaller, and there’s inconsistency. “I normally need 320 litres of ripe cherry to fill a 60 kg bag of green coffee. This year, most people need 400 litres. Some need 480,” Derio explains. “The volume of cherry is big this year, but I don’t think the volume of green will be.”

Both producers explain buyers will still be able to find good quality volume lots and micro-lots because all the issues detailed here can be managed during post-harvest. But farms will have to sort the coffee a lot more, ending up with more volume of defects and fewer exportable grades.

Latest production forecasts

There’s another tricky thing about the cherry-to-green ratio: it gets in the way of production forecasts. The ones consulted by most traders indicate good/normal volumes for an on-year of the biennial cycle. They’re adjusted regularly, and the latest ones were revised down.

Here are the four main forecasts consulted by buyers:

- USDA: estimated an optimistic production of nearly 70 million 60 kg bags in June. This is the most credible source of data for international buyers.

- CONAB, Brazil’s National Supply Company: predicted 58.8 million bags in May. It’s lower than USDA but still higher than last year’s crop and doesn’t indicate a tight supply.

- IBGE, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics: forecasted 61.4 million bags in June, in line with CONAB.

- Safras & Mercado: the agribusiness consulting firm, one of the most respected Brazilian sources abroad, reviewed its forecast down to 66 million bags in July, mainly because of Canephora (11% decline from the previous estimate).

The coffee market is reacting strongly to every forecast revision announced in the news. The balance between supply and demand is tight mainly because of Vietnam, with buyers bolting to Brazil’s Canephora and Arabica grinders.

The tight market is also why Brazilian coffee exports hit records in 2024, choking the port of Vitória in Espírito Santo. In many ways, high exports are a good thing. It indicates producers are selling when they could be waiting for better prices. But it also shows that Brazilian internal stocks are being rinsed.

Exports have been so high that what was left from 2023 is being sold. This is a year when the country expected to rebuild its domestic stocks, but that’s probably not gonna happen. So what? Well, low stock levels reduce the volume on offer until the end of the cycle in June 2025 and contribute to keeping the market’s baseline high.

Market corrections vs behaviour changes

All these factors support higher-than-average prices. This doesn’t mean there won’t be volatility. Last week, futures prices dropped by $0.13/lb. The American dollar got stronger against the Brazilian real, ICE-monitored stocks rose to a one-year high, and investment funds started liquidating their positions and looking for their assets elsewhere.

Analysts call this type of movement a “market correction,” and it’s the kind of variation we should expect to keep happening. But in Brazil, no one expects a significant change in market behaviour that could shift coffee prices to a different baseline (like below $2.00/lb, for example).

According to Gil Barabach, a consultant at Safras & Mercado, a behaviour change will only come when we hear news about the next harvest in Brazil and Vietnam. In both cases, this will happen in the last three months of the year when coffee trees in Brazil flower and Vietnam’s harvest starts.

Once again, traders are looking at the weather in these two major origins to assess future market movements. The world is likely to enter a period of La Niña between August and October. La Niña is associated with stronger crops and could bring rain back to a drought-stricken Vietnam. However, it could also delay spring showers in Brazil and, as a result, coffee flowering.

Let’s wrap it up

So, what does this all mean for you? If you’re buying coffee, expect some fluctuations in price and availability. Keep an eye on weather forecasts and production reports from Brazil and Vietnam. And remember, the quality of the coffee you get might require more sorting on the producer’s end, which could influence the final cost.

Got more questions? We’re here to help you navigate this market. Reach out to your account manager or talk directly with producers through the platform. We’re here to make sure you get the best quality coffee for your needs, even in a challenging year like this one.

Important dates

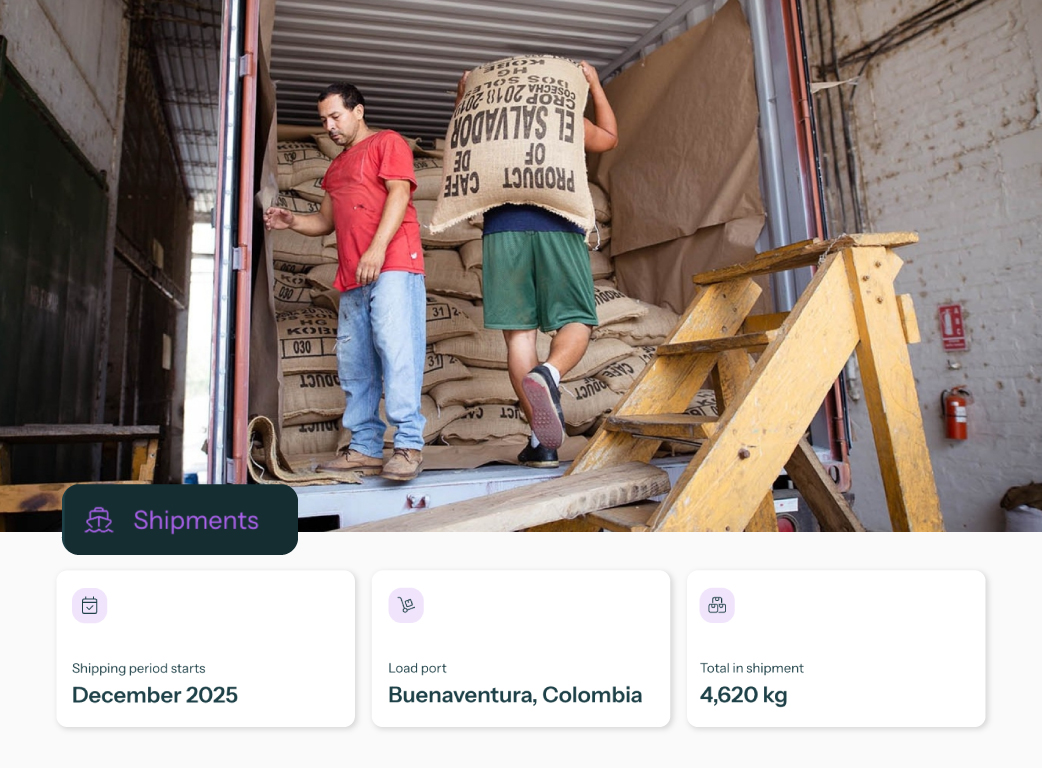

We have many shared shipments from Brazil this season. You can add orders of any size to these containers. Orders of 100+ bags can also be shipped alone at the best time for your roastery. Here are the key dates:

Europe (Bremen)

First containers: last orders by mid-September for December and January releases.

Mid-season containers: last orders by mid-October for January and February releases.

Last containers: last orders by mid-November for March releases.

United Kingdom

Last orders by mid-October for February releases.

United States

Last orders by mid-November for February and March releases.

.png)